Playing around with IPv4

Somehow, majority of us might be familiar with Internet Protocol (hereafter IP), its two versions - v4 & v6 and the fact that IPv4 is subjected to address exhaustion (4,294,967,296 addresses) due to which we use the concept of Network Address Translation (hereafter NAT) or more simply, private networks. This article does not aim at explaining IP, its classes, subnetting, NAT, etc. Rather, it aims at exploring some lesser known specifications and properties of this protocol that we came across through tinkering and experimenting around it.

If you are not familiar with the fundamentals of networking (OSI model, TCP/IP, etc.) this article is of least importance to you for now. I would strongly recommend you to get familiar with networking fundamentals first and then come back here.

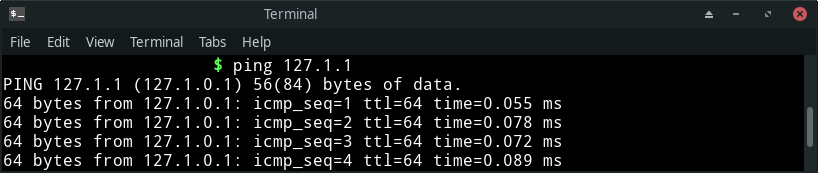

There is no place like 127.0.0.1 & 127.0.0.2 & 127.0.0.3 & … maybe 127.255.255.254?

If you have ever read this quote as a geek or a nerd, you must exactly be knowing what’s being conveyed here. Don’t you? If you really don’t, there’s a popular quote, “There is no place like home”. The geeks from computer sciences tweaked it a bit to replace home with 127.0.0.1 as it is a loopback address which basically represents the system that generates the request to it. This system is what we are in control of and hence is comparable to home.

But due to the fact that 127.0.0.1 is so much escalated through such quotes and examples all over the web, it is believed by many people that this is the only loopback address (or home address) when in actual the entire network of 127.0.0.0/8 acts in the same manner. This means, that from 127.0.0.1, all the way up to 127.225.225.224, every single IPv4 address is a loopback address.

To put it simple, it’s like more than 16 million addresses pointing to the same place.

What’s the point?

Let’s assume a situation where Alice wants to deploy multiple instances of a same services (let’s say httpd) locally for some testing. One way out is to have one instance listen on 80/TCP and the other one on 8080/TCP. This way she would visit http://127.0.0.1:80 to access the first one and http://127.0.0.1:8080 to access the other one. But, why to switch to some non standard port when IPv4 provides millions of loopback addresses? Alice in this scenario can also configure these two instances to listen on 127.0.0.1:80 and 127.0.0.2:80 respectively. That would make her keep a track of http://127.0.0.1 and http://127.0.0.2. This is a more cleaner and efficient way to manage and configure local deployments for testing specially when such instances starts to increase in numbers.

Let’s dive into the A.B.C.D.

We know that the standard representation of an IPv4 address consists of 32-bit address space. These 32 bits are divided into four octets separated using a . or dot.

Let’s see how this is done. Let’s take 192.168.1.1 for this example. Observing it from the A.B.C.D form of representation,

A=192B=168C=1D=1

Each alphabet consist of a 8-bit binary value. That means it can consist of a value from 00000000 to 11111111. If we convert it into decimal, that’s 0 to 255.

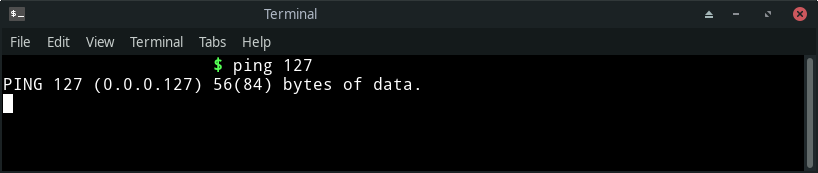

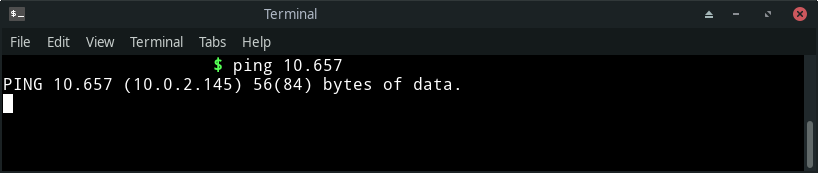

That’s standard. But it doesn’t mean there are no other ways around. We can literally play around this A.B.C.D representation of IPv4. What if I say, 127.1 is a valid form of representation of an IPv4 address? or what about 10.657? I know I said it can only range from 0 to 255 and there have to be four of these separated with a . but let’s see how this is being possible.

When fewer than four numbers are specified in the address in dotted form of representation (D, A.D or A.B.D), the last value (D) is treated as an integer of as many bytes as are required to fill out the address to four octets. This results in concluding the following:

D=0.0.0.DA.D=A.0.0.DA.B.D=A.B.0.D

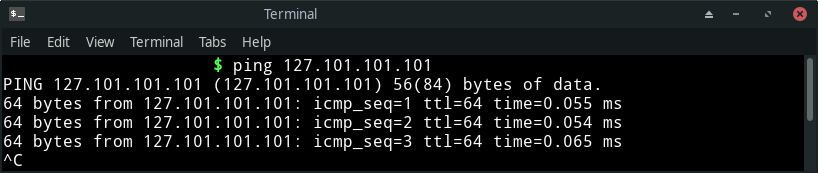

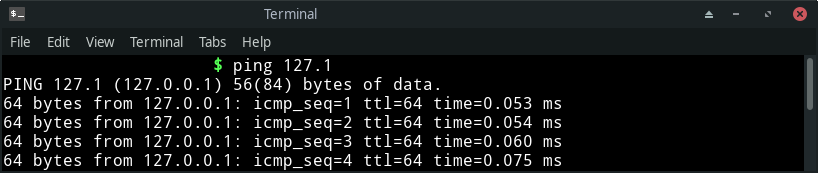

Let’s see how 127.1 is a valid IPv4 as well.

127.1 is in the from A.D which gets resolved into the form A.0.0.D and hence 127.0.0.1

Overflow

You might still be wondering that 10.657 is also in the form A.D which would get resolved into 10.0.0.657 but that would violate the fact that value for each octet must not be greater than 255. That’s true and that is why D when exceeded beyond 255 would always use the 0(s) before it to balance out. And this happens in the following manner:

0in place ofAif any = quotient ofD/(256*256*256)0in place ofBif any = quotient of(remainder from above)/(256*256)0in place ofCif any = quotient of(remainder from above)/(256)D= remainder from above

This concept applies to other forms (D and A.B.D) as well.

In this very case, D = 657. Since there is no 0 in place of A and instead 10 exist, the first step is skipped. Since no division occurred, the remainder remains 657. Dividing this by 256*256 would result in 0 as the quotient and 657 as the remainder. So, 0 in place of B would remain 0 and remainder again remains 657. Dividing it with 256 results in 2 as the quotient which would be the value of 0 in place of C and remainder comes out to be 145 which would become the new value of D.

All that results in 10.0.2.145.

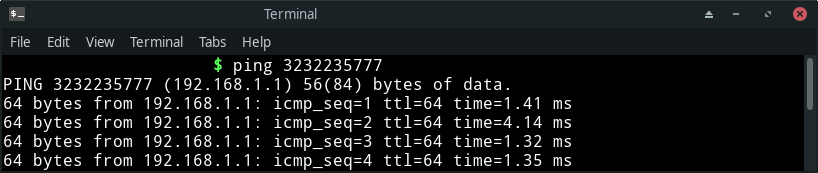

Undotted IPv4

The concepts explained above can conclude the fact that an IPv4 address can exist without any dots at all. That would be a D form. Let’s take 3232235777 for an example. After getting resolved to 0.0.0.D, this would be 0.0.0.3232235777.

Now applying the concept of overflow to it since 3232235777 clearly exceeds 255:

0in place ofAif any = quotient ofD/(256*256*256)=1920in place ofBif any = quotient of(remainder from above)/(256*256)=1680in place ofCif any = quotient of(remainder from above)/(256)=1D= remainder from above =1

And that results in 192.168.1.1.

With that, it can be concluded that there are indeed many forms in which IPv4 addresses can be represented.

It isn’t always numbers.

So far, we have discussed that a standard representation of an IPv4 address has four octets or four parts of 8 bits each, separated with a .. Each part can range from 0-255 in decimal. But value of each of these octets or parts can also be in hexadecimal or octal notation.

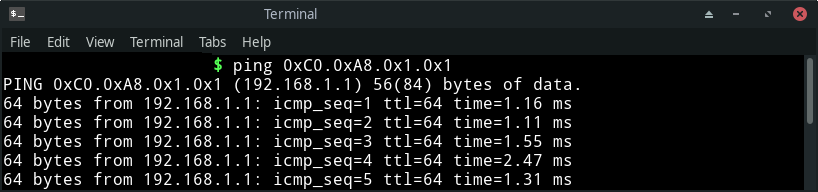

Hexadecimal Notation

Let’s consider 192.168.1.1 again for an example. Converting each part or octet into hex results into 0xC0.0xA8.0x1.0x1. When representing in hexadecimal notation, it is required to prefix the value with 0x.

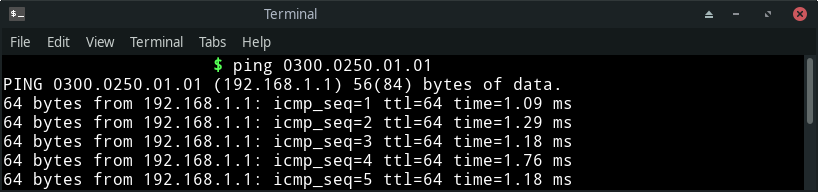

Octal Notation

Considering the same address for an example, the octal representation would be 0300.0250.01.01. When representing in octal notation, it is required to prefix the value with 0.

Time for hybridization

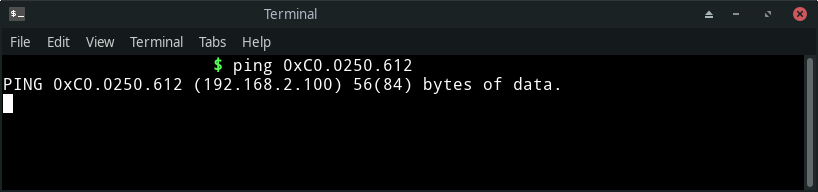

To sum up everything, we can use any form of representation with any form of notation.

This means, 0xC0.0250.612 is also a valid representation of an IPv4 address which is in the from A.B.D where A has a value in hexadecimal notation, B has a value in octal notation and D has a value in decimal notation. But since D exceed 255, it would overflow into the 0 that would come in place of C.

I’ll leave the explanation of the calculations for this one up to you.

How is this useful?

How does it make sense to be aware of whatsoever is being discussed in this article? Why to bother and understand all of these complexities when there is a standard representation and that too quite convenient? As a penetration tester or someone who is always fuzzing around inputs, having this knowledge can bypass a blacklisting provided there is no validation for standard representation on the input. For an example, if a web application blocks 127.0.0.1 as an input on the application level, 127.1 can be supplied instead. In case, the input does not get validated for the standard representation of A.B.C.D, this would get resolved into 127.0.0.1 and fulfill the purpose of bypassing a blacklisting. Please note that this would never bypass a network level restrictions as every representation of an IPv4 address gets converted into 32-bit binary before it becomes ready to be transported over a network. And no matter what representation gets passed into an input, the other system on the network that gets the 32-bit binary form, would always convert it into the standard representation. So. 192.168.1 would always reach a firewall or a router as 192.168.0.1.